By Eric Andersen

Published: Oct. 4, 2014

“The dykes around George Magee’s land at the mouth of the [Squamish] river, which have lately been completed, stood the test of the late high water to perfection”, reported a Vancouver newspaper on October 12, 1892. Richmond farmer George Magee had acquired the delta lands below Pemberton Avenue after they were abandoned by original pre-emptors, Burrard Inlet sawmilling interests.

Our Pemberton Avenue was first a Magee ranch dyke built along a line separating his Lot 486 from Squamish Island Indian Reserve to the north. By 1903 Magee’s dyking projects encompassed over 500 acres of delta lands east of the river’s central branch. The Squamish delta ranch was to be a successful agricultural and real estate venture for George Magee.

Members of the large Magee family were significant pioneers of B.C., and of this corridor. Brother-in-law Robert Carson, rancher at Pavilion, had been the first to drive cattle down the “Howe Sound Trail” in the 1870s when the potential of the delta was identified.

At the time he began the local dyking projects, George was also investing in the Squamish Valley Hops Raising Co., Howe Sound timber ventures, a Lulu Island electric rail proposal and business interests in California. George Magee had been a principle mover in dyking and drainage schemes in Richmond, where there was experience with, and controversy over, employing Chinese immigrants for this work.

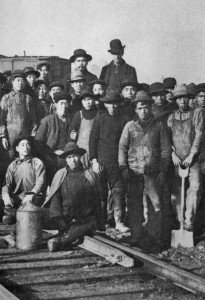

At Squamish, he may have used the services of Chinese contractors and crews familiar from Richmond. During the 1880s as many as 15,000 Chinese men had been employed building the western end of the CPR. When railway contracts were finished many stayed, joining seasonal cannery workers on the coast to form a large available labour pool.

Here in our valley, Chinese workers were also employed in the hop fields and in logging. It is remembered they were brought in to handle the explosives, when river log jams needed to be broken up.

Most Chinese immigrants came from the Pearl River delta of Guangdong province. Their community was a “bachelor society”, with many wives and families still in China. So, their own stories have not been passed down. However, their dykes have survived – now, since major 1970s food protection upgrades, as “heritage dykes” and interesting estuary trails to explore.