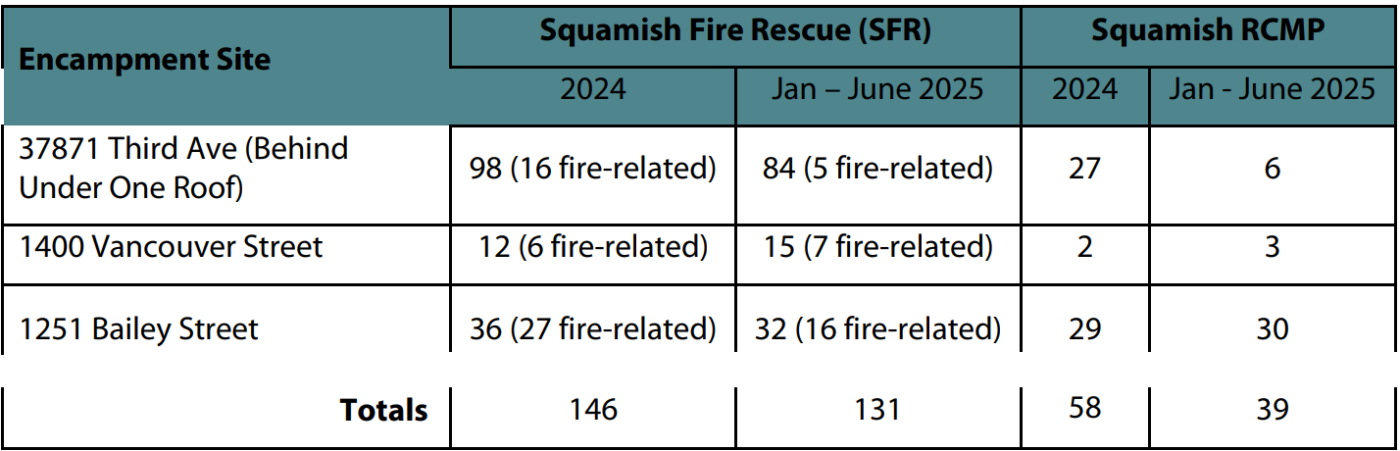

Squamish emergency services responded 236 times to three downtown encampments last year, according to a report by the District of Squamish that was presented to council last week.

District staff say the 2024 tally—which included 146 calls for Squamish Fire Rescue, 58 RCMP files and 32 Community Bylaw Services complaints—came from just three entrenched camps behind Under One Roof, near 1400 Vancouver Street and beside 1251 Bailey Street. Those sites are among roughly eight encampments staff are actively monitoring; there are encampments at the Squamish airport and the landfill.

From January to June, bylaw officers have already handled 56 complaints—almost matching last year’s total of 62—while fire crews have responded to eight significant blazes in tents and trailers. According to the report, nearly all camps contain propane heaters, piles of debris and clusters of near‑empty cylinders, creating a “significant fire hazard,” especially in wooded areas that border critical infrastructure.

“Staff are actively monitoring approximately eight encampments, though that number is fluid as encampment occupants establish, join, leave, or abandon encampment sites frequently,” the report notes. “Also, given the unique geography of Squamish, many encampments may be located in the dense wildland-urban interface that easily conceals these sites.”

Police are also fielding more calls for disturbances, wellness checks, theft and suspicious activity, prompting regular joint visits with bylaw and outreach teams. Staff safety has emerged as a key concern: loose dogs, improvised booby traps and open drug use mean employees must attend in pairs and often request RCMP backup.

Wildlife conflicts compound the problem. Every camp contains unsecured food and large piles of refuse that attract bears, posing risks to occupants and neighbouring properties. The District does not provide routine garbage or sanitation services, and ad‑hoc clean‑ups often prove futile when camps re‑establish.

Municipal officials note that their options are limited because supportive housing and healthcare fall under provincial jurisdiction, and the legal landscape is shifting. They point to the City of Abbotsford, where a B.C. Supreme Court ruling forced the municipality to meet strict conditions—such as individualized housing plans and long‑term storage—before clearing an encampment, a decision Abbotsford is now appealing on cost and jurisdictional grounds.