By Gagandeep Ghuman

Published: April. 13, 2012

The environmental impact of the Sea to Sky Gondola will be negligible, say the environmental consultants for the gondola. The consultants recently completed a comprehensive study of the project as mandated by the BC Parks.

“We have done an environmental assessment and the impact is minimum. There will be no significant adverse impact of this proposal,” said Dave Williamson and Mike Nelson, the principals of Cascade Environmental, the research group hired by the gondola proponents.

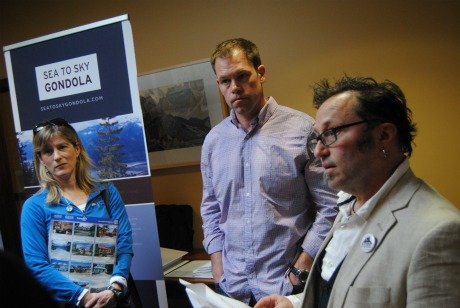

The consultants were interviewed at an informal meeting the Sea to Sky Gondola proponents, Trevor Dunn and David Greenfield, had organised at the Howe Sound Inn on Thursday, April.12.

Alix Pierce-Douglas, the manager of Cascade Environmental, said the proponents have met, even exceeded, the best management practices set out by the province for environmental assessments.

With feedback from BC Parks, the consultants refined their impact assesement to 30 core values, including ecological, environmental, ldlife, and cultural.

“We can’t identify any significant impacts. The foot print here is so small,” Williamson said.

The wildlife won’t be particularly vulnerable, Williamson added.

The research hasn’t identified any significant habitats for falcon nest, or mountain goats, or any other species such as bear, deer, cougars, bob cats, etc.

Mike Nelson said the gondola in itself won’t amplify any chances of bear-human or cougar-human conflicts.

“This is Squamish, we live in bear country, and we know how to manage any potential conflicts,” he said.

Williamson said they have adhered to the best management practices defined by BC Parks for every parameter, be it riparian, wildlife, or vegetation.

“We have been very precautionary, and we have adhered to the best practices. To give you an example, on the Oleson creek, the best practice is to protect water shrews with a 100 metres buffer. We said yes, we will respect that buffer,” he said.

He said a few wetlands have also been identified for protection.

Proponent Trevon Dunn called the recent criticism of the gondola, “disappointing,” but said he is willing to listen and answer his critics with qualified science.

Dunn said he and his partners have been accessible to the community from the get go.

“Perhaps there are a few people who felt they were not consulted, but it’s just the way it is with these big projects,” he said.

A few minutes later, Brian Vincent walked into the room. The animal rights advocate has been fierce, and one might add, a rabid critic, of the gondola.

“They haven’t done a thorough assessment, and they are bringing boat loads of tourists into an area where there are bound to be more conflicts,” he said.

“Unfortunately, it’s the bears and cougars that ultimately pay a price for it,”” Vincent said.

He had a suggestion for the proponents: Close the gondola from spring through summer.

“They laughed at me when I said that, but they are not considering the impacts opening up back country would have,” he said.

Dunn said the assessment has been completed under the stringent guidelines provided by BC Parks.

“We haven’t gone out and counted every bear, but we have far exceeded the standard set by BC Parks,” Dunn responded.

“We will also advise the mountain biking community of the trails that can be used and if there’s a concern, we have the ability to limit lift access,” Dunn noted.

He said people hiking the Chief won’t see any part of the gondola, and a narrow strip of land, just over 2 hectares, will be reclassified as protected land.

He said it’s pertinent to mention the area at the top temrinal was logged, and would probably be logged again in another 30-4o years.

“In our minds, the impact of having hikers will be much less than logging. Basically, we are changing the value of this place from resource to recreation.”

The consulants will soon present their impact assesment report to BC Parks.

Anonymous says

Gagandeep, how disappointing. I thought the goal of reporters was to be fair and objective. For a journalist to call someone a “rabid critic” in a news article is highly inappropriate. Further, why did you not interview BC Parks about the environmental impacts of these types of developments? It up to BC Parks to decide if the impact of this proposal will be negligible are not, not the developer or their consultants. Brian is one of several local residents who has concerns about this project, I don’t think these concerns should be minimized or these residents name called. If the project follows all the proper input processes and everyone is allowed to speak freely and respectfully and then it is further rigorously examined by appropriate government departments, I will be satisfied with the outcome of the application regardless if this development goes ahead or not. Unfortunately BC Parks has decided to waive our opportunity to comment on the removal of Class A Park for a private business so it does not appear this fair and impartial process will happen. I encourage people who want to have input to write to our elected representatives. There is more information on the FOSC website at http://www.friendsofthesquamishchief.wordpress.com

theresa negreiff says

fyi. This is my comment, i had computer problems so thought it did not send and rewrote below.

theresa negreiff says

Gagandeep, how disappointing. “Rabid critic” sounds like name calling to me, certainly inappropriate if you were attempting to a craft fair and objective article. A fair and objective article could have also included an interview with BC Parks to find out more about the environmental impact assessment process and whether S2S Gondola Corporation has indeed met or exceeded the requirements. An impartial public assessment needs to determine if there will be minimal impacts to our Park and surrounding wilderness, not consultants being paid by the developer. Personally, I find it hard to believe that carting 3000 tourists each day to a back country location that formerly only saw a handful of people each year “won’t amplify any chances of bear-human or cougar-human conflict” as Cascade Environmental claims. But that’s just me.

Regardless, if I knew that the Province of BC was representing public best interest by insuring an inclusive and impartial review of the proposal which included a public hearing hosted by BC Parks I would be satisfied whether the gondola proposal goes ahead or not. But BC Parks has decided to waive a public hearing and we are not being offered the chance to speak to this proposal. There are people in Squamish and beyond who are concerned that the suggested benefits of this proposal are not enough to outweigh all that we lose if it goes ahead.

All viewpoints deserve to be heard and addressed respectfully, (not with the eye rolling and snickers I saw from some of the project supporters at the proponent’s meeting on Thursday.) I encourage people to write decision makers and request a proper public hearing from BC Parks. There is more information on the FOSC website at http://www.friendsofthesquamishchief.wordpress.com.

Whether you are in favour of the project or have concerns, we should all be alarmed when government silences our ability to have a say in development in our provincial parks. And please, let’s keep this a respectful conversation. I’m sure we all want what is best for Squamish and our Provincial Parks even if our vision of how we get there might be different. Let’s not resort to name calling.

Brad Hodge says

I’m agnostic about this. I’m opposed to any physical alterations to Chief Park, but otherwise I don’t feel this is a net negative for Squamish. I have my doubts about the economics but I did meet the proponents and felt they were sincere, smart people who have thought this through. One of them looks kind of like Matt Damon. How evil can you be if you look like Matt Damon?

If this was virgin forest I’d be upset. But it’s not, it’s been logged and used for other purposes in the past. I am not really pro-tourism as I don’t believe it delivers the beneftis promised (ask Venetians how they feel about tourism in Venice). But this is basically a ski lift to a viewpoint. Can’t bring myself to get upset over it.

Brian Vincent says

I have submitted the following questions to the gondola developers and appropriate decision-makers.

QUESTIONS ABOUT SEA TO SKY GONDOLA DEVELOPMENT PROPOSAL:

Q. What assessments have been conducted to determine impacts to bears and cougars due to potential interactions between humans and those animals?

Opening up backcountry areas to a flood of visitors will undoubtedly create conflicts between humans and wildlife. Unfortunately, bears and cougars usually pay a fatal price in such circumstances.

Q. Have detailed surveys and mapping of the area to determine numbers and movements of large predators been completed?

Q. What, if any, mitigation measures are in the proposal to protect imperiled amphibians, small mammals, and birds (eg. red-legged frog, western toad, olive-sided flycatcher)?

According to the Georgia Straight, wildlife could be adversely impacted by the gondola: “Several wildlife species at risk could be affected by the gondola corridor. Sea to Sky’s application notes the presence of the northern red-legged frog, which is designated as a species of special concern by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, has been confirmed in the area. Two other species of special concern, the coastal tailed frog and the western toad, are probably present. As well, the company says it’s possible the endangered Pacific water shrew and the threatened olive-sided flycatcher, along with the peregrine falcon, western screech-owl, and band-tailed pigeon—three species of special concern—are in the area.”

Q. What steps will be taken to conserve the area’s biological diversity and environment?

Opening up backcountry areas to people can significantly impact biodiversity, including diminishment of ecosystem integrity and indirect or direct harm to imperiled species and habitat. Localized impacts to wildlife can be significant, especially at the microhabitat level.

Peer-reviewed studies on the impacts of access to backcountry and increased recreational use of more remote areas indicate that projects, like the proposed gondola, can adversely affect wildlife and habitat. For instance, according to a chapter entitled “Indirect Effects of Recreation on Wildlife” published in “Wildlife and Recreationists: Coexistence Through Management And Research:[1]”

“Recreation activities can change the habitat of an animal. This, in turn, affects the behaviour, survival, reproduction, and distribution of individuals. Although more difficult to isolate and study, these indirect impacts may be as serious and long-lasting as direct impacts for many species.”

The authors also noted:

Virtually all types of recreation alter some characteristics of soil, vegetation, or aquatic systems.

Impacts on soil include loss of surface organize horizons, compaction of mineral soil, reductions in macro and total porosity, reductions in infiltration rates, and increases in soil erosion, which, in turn, can adversely affect germination, establishment, growth, and reproduction of plants.

Species composition and vegetation structure change because species and growth forms differ in their ability to tolerate recreational disturbance.

Generally, species richness and diversity declined where recreational impact was pronounced.

Recreation impacts influence important characteristics of animal habitats in turn affecting the quality and quantity of food and living space of animals. Habitat changes can affect behaviour, distribution, survivorship, and reproductive ability of individual animals. Over a longer time period, impacts also occur to the population, community, and ecosystem.

Habitat changes that alter the type, distribution, and food amount available will impact animals. In soil, any activity that removes or reduces overlying organic layers or material, reduces a primary food source for many species.

When food or living space are altered, short-term effects on behaviour, survival, reproduction, and distribution of individual animals will likely cause long-term reactions throughout an animal community. These “trophic cascades” occur because habitat alterations either allow parasites, pathogens, and competitors into an area or they eliminate native species.

Q. Would gondola operators implement seasonal closures during the spring through summer to avoid conflicts with bears with cubs?

Sows are obviously quite protective of cubs. Opening up access to areas where bears may not be as acclimated to human traffic could result in encounters with sows with cubs, leading to potential conflicts between humans and bears, increased stress from bears who flee the area to avoid interactions with humans, and separation of cubs from sows. Studies in places like California have shown high incidents of cub mortality or abandonment after encounters with humans and humans with companion dogs (who sometimes pursue bears).

Q. Will gondola passengers be permitted to take dogs on board? If so, what measures will be in place to ensure dogs do not harass wildlife, including giving chase to bears, bears with cubs, and cougars?

Increasing the number of companion dogs, especially those off-leash, in natural areas can create conflicts with wildlife. Dogs not under the control of their guardians may pursue, maim, and even kill wildlife. Dogs have been known to chase bears with cubs, stressing the animals and creating the potential for separating cubs from sows. Other wildlife, including small mammals, amphibians, and reptiles, are also vulnerable to harassment and/or predation by companion dogs.

Q. What is the total footprint of the project, including gondola construction, infrastructure, concomitant development, and expansive foot and mountain bike traffic extending beyond the actual gondola? Has an assessment be completed to determine how far mountain biking and hiking activities will extend out from the top terminal? Does the environmental analysis provide forecasts for the number of mountain bikers and hikers and user-hours anticipated to recreate in the area?

According to the Straight, “Sea to Sky says it would need to clear a swath of trees to make way for the gondola towers, which would range in height from 5.57 to 23 metres. An estimated 364 to 597 cubic metres of timber would be logged in the swath, which would have an average width of 12 metres. Douglas-fir, western red cedar, and western hemlock are the dominant tree species in the corridor, with the dominant shrubs being salal and red huckleberry. About 30 ‘veteran trees’ with diameters larger than 70 centimetres would be cut down. ” Activities associated with increased access to the area, including hiking and biking, will have impacts far beyond the actual structural footprint of the gondola and associated development.

QUESTIONS ABOUT IMPACTS OF MOUNTAIN BIKING MADE MORE ACCESSIBLE BY GONDOLA

Q. Will passengers be permitted to carry mountain bikes onto the gondola?

Q. Has any analysis been completed to assess potential impacts from increased vehicular traffic in areas accessed by the gondola?

Q. What analysis has been conducted to assess the impacts of mountain biking to bears with cubs, potential increases in stress to those animals especially in early spring when bears must reserve energy for feeding, and to cougars, whose chase instinct can be triggered from fast moving traffic?

Q. What steps will be taken to prevent or mitigate impacts from pedestrian and mountain bike traffic on soils and vegetation?

Q. What steps will be taken to prevent the construction of illegal and informal mountain bike trails?

Increasing pedestrian and mountain bike traffic can have adverse impacts to soils and vegetation, including soil compaction, vegetation removal, potential changes in micorhabitats and microclimates, behavioral changes in wildlife, including increases in stress, alterations in foraging, nesting, hunting, and movements, and increased conflicts with wildlife due to access to backcountry areas.

According to a 2008 US Department of Agriculture publication, “Understanding and Managing Backcountry Recreation Impacts on Terrestrial Wildlife[2]” increased mountain biking and access to backcountry areas can impact wildlife and habitat. The report noted:

Increasing levels of recreational use in wilderness, backcountry, and roadless areas has the potential to impact wildlife species, including those that depend on these protected areas for survival. Wildlife and wilderness managers will be more successful at reducing these impacts if they understand the potential impacts, factors affecting the magnitude of impacts, and available management strategies and implementation methods.

Federal land management agencies have recognized the importance of incorporating the best available scientific knowledge into management decisions.

The large increase in outdoor recreation activity over the last 50 years has been recognized as a potentially serious threat to North American wildlife populations.

Wilderness often provides a refuge for wildlife amid a matrix of more intensively developed lands, and is especially valuable for wide-ranging species that are sensitive to human disturbance and those that depend on special habitats found predominantly in wilderness.

Impacts of recreation on wildlife include increased energetic demands during critical periods of the year, loss of habitat through avoidance of areas of human activity, exposure to predators while avoiding humans, and loss of habitat through changes in vegetation resulting from recreation activities. If widespread, cumulative impacts on individuals of a species may ultimately affect local and regional populations. Changes in species’ populations may affect wildlife communities, especially if the impacted species have strong interactions with other species.

Chronic exposure to noise can result in physiological effects such as elevated stress hormone levels, reproductive failure, and increased energy use. Behavioral effects include changes in habitat use, increased exposure to predators, and reduced parental care. Numerous examples of observed physiological and behavioral effects are provided from the literature.

Although many backcountry recreational activities are often referred to as “nonconsumptive,” these activities can impact natural resources such as wildlife. Furthermore, the potential for these impacts has grown in recent years with the large increase in wilderness recreational use, ecotourism, and the significant growth of outdoor recreation in general.

Species with small home ranges and specific habitat requirements may be highly vulnerable to recreational activities in their habitat.

The authors suggest that prolonged or chronic stressors (for example, recreational disturbances) can result in an energy deficit for an individual, prompting an “emergency life history stage” (ELHS). During an ELHS, an animal may postpone or abandon its normal current life history stage (for example, reproduction) until a positive energy balance can be restored.

Disturbance frequency thresholds, above which impacts can occur, have been documented. Although disturbance is often considered to be most detrimental during the breeding season, disturbance at other times of the year, such as winter, can have equally severe effects.

Indirect impacts result from habitat modification and pollution, and direct impacts occur due to exploitation and disturbance. Disturbance has short-term effects on wildlife behavior, but repeated disturbance can have long-term effects on individuals, populations, and communities.

Recreation can potentially impact wildlife on three levels—individual, population, and community. Most studies have measured individual responses to disturbance. If an activity elicits a significant behavioral response from individuals, occurs frequently, and/or is widespread, long-term impacts to the reproduction and survival of individuals is possible.

Below are additional findings about mountain biking impacts to natural areas, including[3]:

Significant damage to natural areas can occur when bikers, or other users, go cross-country off track (Foreman 2003). The creation of informal trails increases the amount of land, fauna and flora subject to impact by adding new trails or widening existing trails (Cessford 2003, Marion 2007, pers. comm., 30th August). Informal trails are neither planned nor approved before construction. Therefore, they may inadvertently impact on heritage areas, rare and or priority flora populations, threatened plant communities, spread weeds or encroach on water catchments (Annear 2007, pers. comm. 30th October, Marion & Wimpey 2007). Informal trails can be created very quickly with a substantial amount of vegetation and soil impacted occurring in the first year of their development.

Such impacts can be general trail erosion, reduction in water quality, disruption of wildlife and changes to vegetation.

Mountain bikes can cause different types of erosion to other users (Figure 1), (Horn et al. 1994, Cessford 1995, Foreman 2003, IMBA 2007). Breaking and sliding activities loosen track surfaces, displace soil down slopes and create ruts, berms or cupped trails. Tyre tracks are continuous and can therefore form ruts and long rills through which it is easier for water to flow exacerbating erosional losses (Horn et al. 1994, Foreman 2003).

NOTES:

[1]http://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr&id=BRbBAvLwQlAC&oi=fnd&pg=PA183&dq=backcountry+environmental+impacts+wildlife++increased+access&ots=tLvUVRFvDF&sig=gfaSmHcjwII2V-HAHecPuyC8WzI&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

[2] http://leopold.wilderness.net/research/fprojects/F004.htm

[3]http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q&esrc=s&source=web&cd=8&ved=0CFkQFjAH&url=http%3A%2F%2Fresearchrepository.murdoch.edu.au%2F2637%2F1%2Fmountain_bike_activity_in_natural_areas.pdf&ei=2FKGT_L_B8_KiQK24fTHDw&usg=AFQjCNFNmRtwwjgaJA7hvlW1_hpIgmi1mA&sig2=C55g-_5t5iMG6hlo4hIRGg

http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q&esrc=s&source=web&cd=8&ved=0CFkQFjAH&url=http%3A%2F%2Fresearc

http://www.google.com

Elliot says

Theresa. I respect you have your own personal opinion, but please define this “removal of Class A park” language. Sounds like sensationalism. If it is simply permission to put concrete tower bases on a section of the hill to get to the other side, then it should be portrayed as such. I’ve hiked on Whistler under the gondola, and it is in no way disturbing to the animals. They are thriving around the lift lines. The only valid complaint comes from humans worried about the change in their “view”. Gondolas are quiet, electric, non-polluting means of transportation. It’s not an industrial facility going up there.

theresa negreiff says

Hi Elliot, thanks for your note.

I don’t think its sensationalism, just factual. BC Parks has to remove land from the Park if they want to allow the logging of trees and the placement of gondola towers because the BC Parks Act forbids this activity in a Class A Park. Feel free to check the links below. My complaint is that BC Parks is changing their own laws and signing off our publically owned land (that many people fought to have protected for years before it was designated a Park) for a private commercial venture and they have waived our right to ask question about this removal of protected public land. Its not the first time Park boundaries have been changed for a business to operate but it is unusual for a public hearing to be waived. Whistler is not a Provincial Park, so a different issue altogether my mind.

The BC Parks website (http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/bcparks/planning/bound_adj_policy.html )

states:

“Periodically, within provincial parks, land uses are proposed involving activities that are not permissible under the Park Act. The Minister of Environment will consider such proposals where the public interest may warrant modifying park boundaries to remove the affected area from the park.”

This is the specific section of the Park Act that says Natural Resources must not be altered.

http://www.bclaws.ca/EPLibraries/bclaws_new/document/ID/freeside/00_96344_01#section9

I hope that clarifies things for you. You can also check out the link to this Georgia Straight article where a BC Parks Manager refers to the proposed gondola towers being inconsistent with Class A Park uses.

http://www.straight.com/article-634541/vancouver/gondola-split-chief-park