Photo: Environment Canada

By Gagandeep Ghuman

Published: Oct 11, 2013

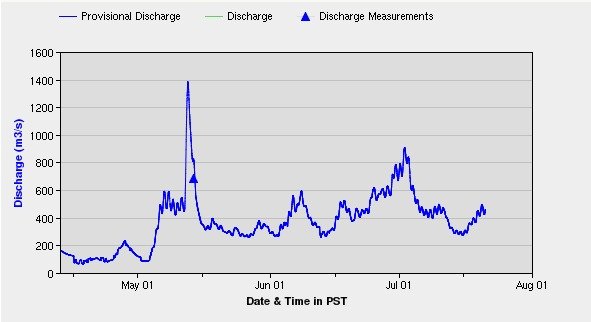

Those in charge of protecting the dike take note: On May 13 this year, the Squamish River surged up to 1400 cubic meters per second, highly uncommon for this time of the year.

Flows over 1,000 cubic metres are rare, and it’s unusual to have a peak like this in spring.

Normally, this happens only in the autumn rain storms, and then again only every few years, according to an expert who has studied the Squamish River delta for the past six years.

“Squamish is geology on steroids.” Prof. Clarke

“It is unusual to have a peak like that in the spring – but not unheard of,” said Hughes Clarke, a researcher with the University of New Brunswick.

Prof. Clarke, along with his students, stayed for five months in Squamish in 2011 to study turbidity currents triggered by underwater landslides on the Squamish delta.

The Squamish River carries an incredible amount of sediment, dumping about a million cubic meters every year into the fjord.

Wherever sediment is deposited very rapidly the area is more prone to underwater landslides.

The ones that Hughes Clarke is monitoring can occur several times a week, especially when the river surges and/or the largest spring tides happen.

Photo: Submitted

These landslides are small in volume, but create underwater flows that can go for tens of kilometers, down the Howe Sound past Woodfibre and Britannia Beach.

From the surface, nothing can be seen even though this is going on right underneath the kite boarders.

New sonar techniques, utilized by Hughes Clarke’s group, are for the first time allowing scientists to examine these rare natural events.

For the scientists from Japan and the UK who visited this year, the Squamish delta is a unique place to see flows that normally only happens every few thousand years in the deep ocean, he said.

“Squamish is geology on steroids,” Clarke said.

Clarke said the landslides and flows that happen regularly are no danger to the town as the volumes are small.

But anywhere in BC that has large deposits of recent sediments is liable to have much larger events that could generate tsunamis.

This happened in 1974 and 1975 in Kitimat, where a 7m high wave damaged infrastructure. The reason for the trigger is not known and it wasn’t an earthquake.

The biggest concern is that these same areas are especially susceptible if a mega-thrust earthquake occurs. The last one was in 1700 and they have a typical repeat interval of 400 to 500 years.

Squamish is protected from tsunamis generated by bigger earthquakes out in the pacific as the wave has to come around through the Gulf Islands and Georgia Strait.

But an earthquake inside the Georgia Basin, could generate local tsunamis from collapsing recent deposits of sediment like the Squamish delta.

Rapid growth in Delta

Because of excessive sedimentation, the delta is growing rapidly both into the Howe Sound and sideways across the mouth of the Squamish Terminals.

As it grows, it will require increased dredging of the western terminal docks.

Eventually in a few decades, it may not be economical to maintain the docks, Clarke said.

“They are going to have to keep digging and about 20-30 years from now, it would be too expensive,” he said.

President and CEO of Squamish Terminals, Ron Anderson, said he is aware of Prof. Clarke’s work.

He said the Squamish Terminal monitors water depths on a ‘reasonably regular basis’.

“If there is a question of infilling from silt that could impact the vessel safety, we will commission a dredge,” he said.

He said a maintenance dredge is expected to happen this fall.

About eight years ago, the Terminal noticed a shift in the river bank as a result of the collapse of sedimentation.

These shifts are long term, and this could mean hundreds of years from now, Andersons said.

On the possibility of an earthquake or Tsunami impact, Anderson noted that these events will likely impact the town and the lower mainland as much as it would impact the Terminals.

“We always hope that this would be minimal for everyone,” he said.