Photo: Gagandeep Ghuman

By Gagandeep Ghuman

Published: Feb. 22, 2014

‘May you forget your own mother tongue’

This curse in Punjab says a lot about the value Sikhs place in language:

For the last three years, Squamish Sikhs have made an effort to ward that curse off their Canadian born kids.

“Canada and English are his future, but I want him to remember Punjabi and Punjab too.” Manjinder Gill.

Photo: Gagandeep Ghuman

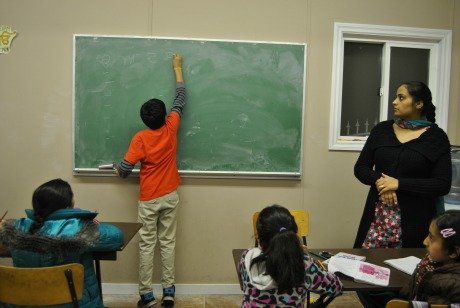

For two days every week, the Sikh temple on Fifth Ave. rings out with the sounds of Punjabi alphabets as kids learn the language their parents hope will keep them connected to their culture.

One a recent Monday evening, Rajveer Tiwana taught a class of 20 young students the basic Punjabi alphabets: Oorha, Aira, Eeerhee.

The young learners follow a syllabus set by Surrey’s Khalsa school. In about three months, the students tend to understand the basic vocabulary.

It’s a one-year course, although Rajveer says some of her students have stayed on for three years.

Sustaining interest is a challenge for both students and parents.

“If the parents are committed, we will see the students will last longer,” she says.

She hopes more first-generation Canadians will learn Punjabi as a way to connect to their roots.

Language as a bridge to culture is a common refrain among many Sikhs living in Canada.

Punjabi, one of the 28 official languages in India, is spoken mainly in Punjab, a province in Northern India.

The dominant religion of that province is Sikhism and the Sikhs diaspora is now spread across the world, with a long history in Canada and its West Coast.

Partly because they are a minority in India, anxiety over loss of culture and language is deep rooted in the Sikh psyche.

Immigration to Canada amplifies these anxieties.

That anxiety is touched in the way cultural purists in Punjab talk about an imminent threat to Punjabi by English, once the language of imperialism, now the idiom of global commerce.

These anxieties and the desire for reconnection first inspired the local Sikh community to start a Punjabi language school in 2009.

Squamish Sikh Society committee member, Ram Singh, said he wants the kids to learn English and French, but also not forget their roots—Punjabi.

“If they know Punjabi, they will know their culture, and which means they can understand their own history,” Ram Singh said.

The Sikh society charges a small fee for the classes.

Seeing his son ten-year-old son, Jashan, learn speak and write Punjabi makes Manjinder Singh Gill proud.

Raising Jashn as bilingual will sharpen his cognitive abilities, but will also connect him to his parent’s motherland, Gill hopes.

“Canada and English are his future, but I want him to remember Punjabi and Punjab too,” Gill said.