By Gagandeep Ghuman

Published: March 23, 2015

There is hardly anyone in Squamish who won’t know of Alice, the lake; but there are very few left who know of Alice the woman. Today, the name Alice seems a fact as natural as the lake. We rarely separate the two. A little more than a century ago, the lake and Alice were two entirely different entities. And between them lie one of the many histories of Squamish: how a people came and slowly made the land theirs—by discovering and then naming places, trying to build personal bonds with an alien land. Alice and Edith lakes are two entry points into the now hazy history of the town. Who were Alice and Edith? We know they were not lake fairies or the resident water spirits. They were real people, among those who had come here to settle down. What did they do to have the lakes named after them?

Squamish in those days was not the attractive destination it has become now. It was a hard place where people spent whole lives wrestling with lumber and hay. When Charles Rose named the lake after his wife Alice in the late nineteenth century, he was stamping his claim on a piece of land to which he had, as it were, got married. The lake must have been as welcome a reprieve for him from his daily grind as the company of his wife. It is understandable that an adoring husband named the lake after his wife, but why did everyone followed him into calling it by that name?

All history is an intertwining of the private and the public. Exploring daily lives of early settlers offers us insights into the making of a community, if not a nation. Lives of Charles and Alice were among the building blocks of our present community, and Alice Lake was a sign of things to come, a heralder of Squamish as the recreation capital.

Alice can be seen in one of the oldest-known photograph taken at Squamish by a photographer likely employed by the hops company, according to historian Eric Andersen. The boat is the SS Burt, the year is 1894, and the occasion is arrival of people associated with Squamish Valley Hops Raising Co. Only a part of her face is visible, but it wears a smile, as if she is happy to have arrived in Newport, her adopted home that was to be called Squamish.

Alice came to Squamish with her husband, Charles Rose, who had found a job with the Squamish Hop Ranch Company. It was a growing business in the Valley with the largest being the Squamish Valley Hop Ranch, a 260-acre farm located where there is the Eagle Run subdivision now. The Squamish Valley Hop Ranch was founded by Dr. Bell-Irving and William Shannon. While Charles worked at the Squamish Valley Hop Co. ranch, Alice was the ranch cook. They built a log house alongside the slough by the hop ranch. Four years later, Charles became the manager of the hop ranch. Also in the S.S. Burt picture is her close friend, Annie Edwards, who was married to the early pioneer Henry Judd. They knew each other from Vancouver and Alice asked her to come up to the ranch for a visit. Squamish Valley abounded with bachelors and Alice was a notorious match-maker, writes Philip Judd in his book, Judds of the Squamish Valley. Philip, who lives in Victoria now, is son of Earl Judd and grandson of Henry Judd.

Alice was clearly more than just a cook. From history books, interviews, and old newspaper clippings, it’s easy to imagine a woman who was a community connector, a match-maker and someone fond of entertaining friends. Annie Edwards travelled several times to see Alice at the Hop ranch for social get-togethers. People in their best summer dresses would turn up for the tea parties thrown by Alice Rose. She would have been a personable host. In another picture, see her flash a warm smile as she holds a big black umbrella in her left hand with her right hand gently resting on her waist. Sitting in the next row is her friend Annie Edwards, her hand resting on the left shoulder of a male friend.

She must have enjoyed these visits to the Squamish Valley Hop Ranch (present-day Greg Gardner Motors) because she accepted an offer to work for Alice Rose. But this time, she came alone, leaving her old boyfriend in Vancouver. She had a great time going to parties and meeting various men in the Valley. She was well-liked and was nick-named ‘pretty Annie Edwards’.

It’s perhaps at one of these parties thrown by Alice Rose that Annie Edwards met Henry Judd. He wooed her, taking her on canoe trips and buying his first horse. They were both married on December 26, 1894 at the home of Annie Edwards in Vancouver. The couple, however, came to stay in Squamish, building a home in Brackendale.

Photo: Gagandeep Ghuman

Stories like these in local history books are woven into the fabric of Ellen Grant’s daily life. Granddaughter of Henry and Annie Judd, the first European settlers in town, Grant shares an intimate bond with the history of Squamish. She is both the receiver and the raconteur, sharing stories her illustrious family has passed on to her for three generations. In one such story, she recalls her grandmother, Annie Edwards, telling her about a friendship she immortalized in a tree carving on the southern side of the Alice Lake. When she was a teenager, Ellen and her friends looked in vain for the tree that would bear the name of Annie Edwards and Alice Rose.

The tree may have long gone but one of those names has been immortalized with Alice Lake, our popular summer destination.

Alice Rose is believed to be one of the first European women to visit the lake in 1893, but that may not be the only reason why the lake was named after her. It’s even possible that her husband may have named the lake after her.

Why, however, did the community accept it? It could be attributed to the extremely small nature of the community, a new-arrival’s desire to claim a place, and the genial nature of Alice Rose.

Grant remembers snippets of information about Alice Rose passed on to her by her grandmother and mother. She was a fun loving, popular hostess who liked to throw parties, Grant says. “She was someone who connected the community ,” she says. In one of his letters to the family, Harry Judd recalls a fishing trip with his friends to a nearby lake. Grant believes the lake he talks about is Alice Lake, even though he doesn’t call it by that name.

The First Nations have lived in this land for hundreds of thousands of years, but the first European settlers came in the late 19th century. There were several settlers who had preempted land in the Squamish Valley in the 1890s. Families such as Raes, Creeman, McIntosh, Gore, Reid, Eppinger, Judds, Maddils, Baynes and Pattersons had started settling in the Valley. The early pioneers took to hops and potato farming followed gradually by logging. They slowly established a life here, starting a school, followed by a hotel and a post office which were built around 1893. The hop business boomed but it was largely over by World War 1, which may have partly contributed to its demise.

The floods of 1908 had destroyed the Rae and Madill Hop ranches and Charles Rose was out of job, Philip Judd says. Both decided to take a trip to Ontario in the summer of 1909. They sent this postcard from Ontario to Rilla Edwards, which is recorded in the Judds of the Squamish Valley . “Sunday in Winnipeg—Dear Rilla Edwards, as we are here for the day, I will drop you a card. We have had lovely weather for our trip and this is a beautiful day. Got here at seven this morning. Leave half past ten tonight for Toronto. Hope this finds you well. P.S. This is a nice place—went to the park. All well, Charlie and Alice.”

While all modern amenities were available in Squamish, life was secluded at a time when the early pioneers made the town their home. “Life in Squamish was very isolated,” says Clifton Thorne, whose father Fred Thorne managed the Squamish Valley Hop Ranch in 1884. “There used to be a little steam tug come into Squamish every two weeks. ‘Bubble and Squeak’, we called it. There was an old Englishman [who] used to run the store and the post office and he’d take the mail sack and just dump the mail on the floor. ‘There it is,’ he’d say. ‘Get your own mail’.”

The trip up to Squamish from Vancouver was something Fred Thorne never forgot, Cliff recalls. “There were my parents, my two older sisters, me and my little brother. The road was rough and there were stumps all over the place. It was barely wide enough to take the wagon.”

But the isolation also increased the sense of community perhaps. Philip and Ellen Grant remember from conversations with their grandmother Annie Judd a time of picnics and summer parties and hikes to nearby lakes. The Vancouver Daily World reported the settlers came en masse to a picnic at Mashiters on August 26, 1897, and then two years later, reported on another boisterous bash at the Mashiters. It was attended by most of the pioneers: Judd, Madill, MaGee, Chamberlain, Rose, Thorne, Read and Rae. The French Minuet was all the rage and was played many times along with waltzes, two-steps, and other favourites. Mrs. Read rendered a Spanish love song which the paper noted was very much appreciated by all.

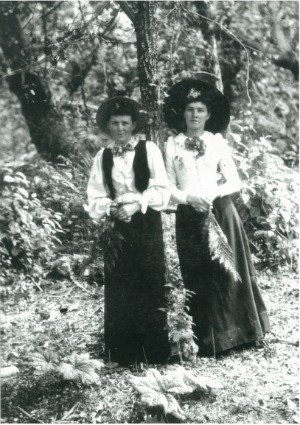

Hiking trips and picnics at the local lakes were a big adventure. In one such trip to Alice Lake, both Alice Rose and Annie Edwards are seen dressed like they are off to a wedding, not a hike. Ellen Grant, the last of the Judds in Squamish, remembers she first saw the Alice Lake as a little child with her grandma, Annie Edwards.

The Judd family, like other members of the community, went there quite often for swimming, fishing, snowshoeing and picnics. By the late 1950s, Alice Lake was a provincial park made possible only by untiring work of volunteers and community leaders such as John Drenka, Dennis DeBeck and Bill Manson. The community had already made improvements the previous year, installing picnic tables and swimming floats, clearing the area for parking and landscaping it. A Squamish Times report quotes John Drenka praising community members such as Eric and David Axen for building the restrooms, A. Hoogenboom for building the change rooms, and to Fred and May Leeworthy of Squamish bakery.

Lack of a swimming pool in the community and a drowning incident in 1949 drove volunteers and community leaders to build the Alice Lake Park for community use, says Eric Andersen. Later, he says, the provincial park was extended by three square miles to include Fawn Lake and Camp Lake, which is now known as Edith Lake. Edith Lake, as anyone who loves nature will tell you, is an oasis of tranquility, a place where we can lose ourselves and come back whole.

That is what Ivor Griffith did almost 70 years ago. It can only be called a quirk of fate, but we may have known Edith Lake by another name had he not lost his voice.

Ivor was the brother of Gwenth Griffith, who was married to Earl Judd, Henry Judd’s only son.

Philip Judd remembers vividly his uncle Ivor’s trip to Squamish and how he came to build a cabin around what was then called Camp Lake, named after Merrill and Ring’s logging camp.

Ivor was a school teacher up the coast near Skeena River who had to quit his job because he lost his voice in the 1930s. Philip Judd recalls in his book how his father helped Ivor build a one-room cabin in Brackendale when he moved to Squamish. “My Dad helped Ivor Griffith build a small one-room cabin on our farm about 100 yards from our house under a Northern Spy Apple Tree.”

During the First World War, Ivor found out he could improve his voice by yelling. His voice had grown worse and he was asked to do yelling exercises to improve his voice. “The exercises embarrassed him, he didn’t like yelling at his sister’s place and he thought he would like to live away from humans,” says Philip Judd.

He started looking for places where he could live and yell freely to regain his voice. He finally found a place around a lake that we know as the Edith Lake.

That place was the old logging camp for Merrill & Ring and the lake was called Camp Lake. Philip Judd tells the story in his book: “When Ivor visited the old campsite in 1941, he found out that the camp had been burned but that some ties and lumber still lay around. Water was still running from an old pipe located in the camp area so he decided that the water supply was still intact. He thought he could live there where he could yell as much as he liked without people hearing him.”

Ivor could also be credited with building the trail from Alice Lake to Edith Lake, then still called Camp Lake. A short distance south of Alice Lake, he built a slope from the abandoned grade to Camp Lake which wound through a narrow valley to the western side of the Edith Lake. He finally built a cabin at the lake, a secluded oasis where he could yell with only bears, cougars and the birds to hear him.

It was Ivor who suggested to Myrtle Judd (Myrtle Herndl after marriage), one of Henry Judd’s daughters, to lay a claim to the land around Edith Lake when he was about to leave town in 1943. He had no legal claim to it and he knew the government could lease the land if an application was made.

It was Myrtle who would later name the lake after one of her eight sisters, Edith Judd.

Myrtle took Ivor’s suggestion seriously and built a nice cabin there which was her home, off and on, for about 20 years. She applied for a lease on three sides of the lake as much as the government would allow. Eventually, she was granted a crown grant over the land, which enabled her to convert Ivor’s shack into a nice cabin.

She added on a new section to the previous one, building a nice log house that had bed at one end and a kitchen stove at the other with one window in it.

“She really liked living besides the lake,” writes Philip Judd. “She could see the tops of the Tantalus Range above the young trees on the western side of the lake.”

Ellen Grant remembers how much Myrtle liked the woods and the beautiful garden she eventually built around the lake. She would also enlist the help of teenagers like Grant in helping her clear the land. The place eventually became a meeting spot for young people and family gatherings because of Myrtle. “She was a really outgoing person and she was a very generous person who pulled in people,” Grant remembers.

It’s hard for Myrtle’s son, Wilfred Herndl, to explain the feeling of staying up at his mom’s cabin on Edith Lake. “It was very peaceful but a wild, wild place,” he recalls. “There were wolves and bears and at night you could almost reach and touch the stars.” It would take half a day to hike up to Edith Lake, Herndlt says, recalling the trips with his mother and friends. But it was worth the walk. “Swimming in the lake was like swimming in a bathtub. We used to fish there, pick blackberry and make blackberry jam,” he remembers.

Myrtle loved living on Edith Lake and it inspired her to paint the mountains and the scenery. But why did Myrtle name the lake after her sister, Edith? For early pioneers invited by the government to homestead and establish a new life in Canada, perhaps naming a place after a loved one was a psychological way to lay claim to the land. Ellen Grant says that Edith was the one who had found the lake and it came to be known initially as Edith’s lake. Her sister Myrtle was the one who made it official when she got the lease on the crown land. Edith Judd was the strong link in the chain that held the family together, Grant recalls. She was the one who started the family letter link, where family members had to write twice in a year, sending a letter to the next person in the family. In naming the lake after her sister, it’s possible that Myrtle would have also been thinking about a name that was the strongest connector.

Historian Eric Andersen says names were solidified in regional maps that the BC government drafted in the 1950s. There would have been public consultation but not with the local First Nations, who also have a strong tradition of naming geographical features.

The popular tourist attraction, Shannon Falls, is named after William Shannon, who was granted a lease to the surrounding land by the government on 1889. It was officially adopted as Shannon Falls on March 3, 1949.

The Squamish Nation name for this fall is Kwékwetxwm. In the rendering of this tale, the mythological hero Xwéch’taal (the serpent slayer) used the falls as an access route in his pursuit of Sínulhka, the dreaded double-headed sea serpent.

The oppression of the residential school system, fewer native language speakers, and a much more oral rather than written tradition may have made it easier for the European pioneer to stamp their identity on new geographical features they discovered. For Myrtle’s son, William Herndlt, naming a geographical feature was not merely about creating a sense of ownership; it was also a proclamation of the settlers’ love for it. “They had a feel for this land and the mountains, and they loved it,” he says.

Though the original history of the Edith lake has completely lost, Squamish Nation member Alice Guss remembers Alice Lake was called ‘a place where the deer gather’. As with other geographical features, the place lost its First Nation name as Europeans took over the land. The successive government further gave official credence to European names. Mt. Garibaldi, for example, was called ch-KAI in the Squamish language, which means a dirty place because the water in the stream (Cheekye River) at that place was muddy. The government revived the First Nation names along the Highway 99 during the Olympics as part of the Sea to Sky Cultural Journey, she says

Jim Harvey says

“The First Nations have lived in this land for hundreds of thousands of years….”is probably closer to 4,000 – 5,000 years.

Tom talk says

Loved the bit about Ivor. A fascinating read on the whole.

jane in bc says

It was like watching a movie on the history of Squamish… vivid, inspiring and such depth! Thanks for writing this.

wn smith says

great story. congratulations. so much history had drowned in the lakes. you retrieved it beautifully. look forward to read more such stories.

The Go-to Man says

Ellen Grant is a valuable resource for our community.

Billy says

Fascinating how tough it was then. Do you mean that First Nations were here TENS of thousands of years ago , rather than HUNDREDS of thousands ?

Rachel says

Fascinating story! Our family came to Squamish in the late 1920’s and I’ve always loved to hear about our town’s history.

heather gee says

Oh Ivor, If only you knew what you had started …… local men are still shouting – even when they are communicating with people standing alongside them. At least I now know the history of this Squamish characteristic.