By Gagandeep Ghuman

Published: Oct 19, 2015

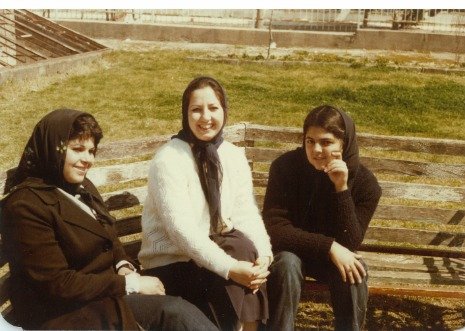

Before the Islamic Revolution of 1979, life in Iran was comparable to any other Western country in Europe, says Mina Dickinson. Stylish clothes and high fashion were the norm and people looked to Paris and Milan for cues on how to dress. When friends and family from America and Canada brought back clothes as gifts, they were usually considered to have arrived late by a year. At her school, Mina recalls, girls would attach zippers on to skirts so they could be taken off when then went out into the public.

“We had many night clubs and people went there and danced all the time. Teheran was comparable to any European city,” she says.

And then came the Islamic revolution — clamping down on individual liberty, segregating men from women and enforcing a strict dress code. While earlier optional, women now had to wear the hijab and cover themselves or face a heavy-handed response from the moral police.

“It was the new law and we all wore it but it was very uncomfortable wearing it in the heat. I hate to cover my head and I hate sweating but we didn’t have any choice,” Mina reminisces in her Dentville home.

What was even more oppressive about the hijab was the fact that it was also strictly enforced on women of all religion, whether they followed Islam or not. Mina was a follower of the Bahai religion but she had no choice but to wear the hijab. She took the lead of her mother, who used to wear the chador, a large piece of cloth that is wrapped around the head and upper body and leaves only the face exposed. But even wearing the chador had its practical problems as one hand had to be kept on the chin to ensure it won’t slip.

Mina remembers the sudden change in rules around head dress meant she and her friends had to spend more money and time with the hairstylist as the hijab and the chador could ruin perfectly done hair. Mina’s mother liked wearing the chador for the sense of safety it provided, but for Mina it made her claustrophobic even though it was more airy garment.

“You not only had to spend more on your hair, it was really uncomfortable because you had to hold it with one hand and the cloth can compromise your vision.

Mina felt resentful about the enforced dress code because she saw it the result of a warped thinking that relied on a very strict and literal interpretation of the Islamic holy book. Eventually, she had to leave Iran because the constitution of Iran doesn’t recognize her Bahai religion. After her husband died, she couldn’t get a job because of religious discrimination and eventually had to leave Iran.

Mina says she believes in individual liberty and freedom and feels Zunera Ishaq should be allowed to wear the niqab at the citizenship ceremony.

“For me, it really comes down to choice and if she wants to wear the niqab, then she should be allowed to do so,” she says.

Recently when Anissa Moussi travelled to France to visit her extended family, she decided to buy some jewellery as a gift for her cousin. But her cousin wouldn’t accept the gift as her father wouldn’t allow her to wear it.

“I was so shocked. This was someone who was a really cool guy I used to play with when I was a little child,” Anissa recalls the spurned gift from an uncle whose life took a fundamentalist turn when he migrated to France from Algeria.

Anissa’s cousins and aunt wear the hijab and her uncle displays an overzealous religiosity, which has its roots in a brief but tumultuous period of Islamisation in Algeria in the early 90s. Head dresses of all kinds were available and were worn by women out of choice, Anissa recalls. But once the Islamists won the elections in 1991, they made it compulsory for women to wear the hijab. Their short-lived reign was enough to scare people into following a strict interpretation of Islamic law—and make hijab compulsory. Anissa says her mothers and her friends didn’t wear the hijab earlier but had to wear it once the Islamist came to power.

“Those who didn’t wear it were severely abused and threatened so many people had no option but to comply with it,” she says.

Members of her own family had started wearing the hijab but that reign of fear was short-lived even though it left many Algerians, just like her uncle, turning to a more rigid idea of Islam. Anissa’s mother travels to Algeria quite often and sees more liberal social mores. She doesn’t wear the hijab, Anissa says, but doesn’t judge those who choose to wear it even though there is no regulation that asks them to.

Anissa spent her formative years in Bahrain, an Island country with a road connection to Saudi Arabia, a country infamous for its unyielding application of Sharia law and its regressive attitudes towards women. Anissa, however, remembers it mostly for its drunk drivers, who travel to Bahrain to drink and show off their wealthy cars. Despite being next door to Saudi Arabia, Bahrain is one of the most liberal countries to grow up in the Gulf, she says. There are no legal repercussions for women going out with their hair exposed, although many women wear for the sake of modesy the hijab or Abbaya, a robe-like dress.

“It’s quite normal to see women wearing Abbaya. 60 to 70 per cent women wear it to be modest and do it out of respect because it’s also a deeply ingrained cultural thing and there is no government rule around it,” she says.

When she visits Bahrain to see friends and family, Anissa says she wears an Abbaya sometimes if she goes to the souk or an open-air market place. Abbaya, a long-robe garment, covers the entire body but not the face and Annisa says she wears it to ward off unwanted attention from men. Many women will take off their Abbaya when they are in an office but may still keep the hijab, the head covering to look modest. To see a woman fully cloaked in a burqa or in a niqab is a rare sight in Bahrain, although fairly common in next door Saudi Arabia, Yemen and Oman.

A woman should be allowed to wear whatever she wants, Anissa says, and doesn’t agree with the government’s assertion that niqab should be taken off during citizenship ceremony.

“I’m sure there are other ways of determining who she is and creative ways to get around the question of identity,” she says.

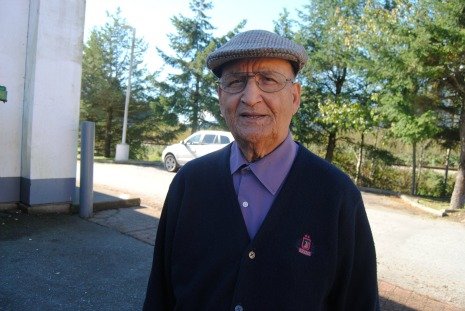

Mohammad Afsar

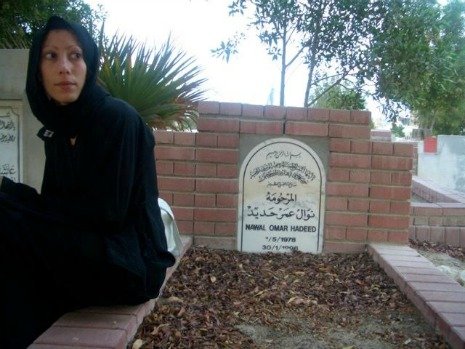

When Mohammad Afsar’s family moved from Pakistani Punjab to Karachi, his mother also packed with her a distinct style of burqa called the Peshawari burqa, worn by women in the neighbouring province of Peshawar.

But as the family immersed themselves in the metropolitan city of Karachi, she never wore it. It was for the Afsar family an alien piece of clothing to begin with. Where Afsar originally grew up, in the Hazara district of the Punjab province, women rarely wore anything that veiled their face. They wore a duppata to cover the hair and sometimes the upper body but a niqab or a burqa as a piece of dress was about as foreign to them as it would be to most people in Squamish.

“No one wore the burqa or niqab in our villages and town in Punjab because we are close-knit communities and there is simply no reason to not show our faces to each other,” Afsar says, recalling his childhood.

When people did see a woman with burqa, they may presume she is more pious but there is nothing religious about it at all, says Afsar. Barring a few provinces close to Afganistan, burqa or niqab wasn’t worn by a large number of Pakistani women. burqa, he says, was imported into Pakistan as a cultural item in the 70s when Pakistani families went to Saudi Arabia chasing petro dollars and brought back Jalbab and the burqa into mainstream Pakistan.

“Some people saw it as sign of piety but we never really thought of it much except that it was mostly driven by middle-eastern culture and I have a problem when someone says it’s something that is religious,” Afsar says.

Afsar says he has studied the issue closely and there is ample evidence put forward by eminent Islamic scholars that there is nothing in the Quran that would require you to cover your face if you are a woman,” he says.

Even at the Mecca, Islam’s holiest city and the birthplace of Prophet Muhammad, the women don’t wear any veil as they pray to God, Afsar says.

While the import of niqab and burqa in Pakistani was partially driven by migration of Pakistanis to the middle-east, it was also aided by an influx of Saudi money into Pakistani madrassas, many of whom ascribed to a rigid, Wahabi sect of Islam.

Even though Pakistan is a considerably diverse country with strong secular liberal influences, Afsar says there has been an increase in Islamic fundamentalism and its roots may lie in the brief but rigid control and re-ordering of society imposed by General Zia-ul-Haq, a ruthless military dictator who ruled Pakistan for a decade and is known for introducing Sharia Law and Islamization of Pakistani society.

“If you read the history and do research, you will find out that the culture of wearing the niqab and the burqa actually started from the middle-eastern countries,” he says.

Aghast at the niqab issue being painted as a matter of religious belief, Afsar says he is disappointed at the recent judgement which allowed Zunera Ishaq to take oath as a Canadian while she was wearing a niqab.

“The niqab goes against the values of gender equality enshrined in our charter and to claim that it’s a religious belief is simple a pretense in my view,” he says.

Growing up in Teheran, Ali Taherinejad, the owner of the local UPS store on Second Ave, says niqab and burqa were alien garments for him and his family. His mother and his sisters didn’t even wear the hijab, let alone the niqab or the burqa. For the sake of modesty, the women did wear the scarf or the chador only when they were venturing out. “It would be considered strange if we saw women wearing a niqab or burqa in Teheran,” he says.

Ali says they were well-aware that women wore burqa in parts of Southern Iran and it wasn’t until he went to Baluchestan, a province in South-West Iran, to study marine engineering that he first saw women dressed in burqas, their head and faces covered by a distinct style of cloth. The style of burqa varies considerably from the one women are forced to wear in Saudi Arabia, which cover the body from head to toe. The one Ali saw and widely prevalent in Southern Iran leaves part of the face visible and has several variations of style and clothing.

As he befriended Balochi friends, Ali says, he gradually realised the Southern style of burqa was more a fashion rather than a religious piece of clothing. “It may have been religious or cultural but now it was more of fancy fashion attire, something that was cosmetic,” he says.

Despite its widespread use as a dress, not everyone wears the burqa even in Southern Iran, which from a practical point of view is also bothersome to wear as the region can get quite hot. Ali says fewer women wear burqa in Southern Iran as social norms around dresses relax and change.

burqa was never meant to be worn by women for religious reasons for there is nowhere in the Quran that mandates the use of such a piece of clothing, he says. “It’s absolutely not compulsory to wear it in Islam and it’s really quite nonsensical to wear the burqa and I really don’t see the reason to cover the body in such a way,” he says.

Ali says he finds the argument that women wear it to protect themselves from men quite demeaning and insulting to both sexes and especially to men. “To see it as a shield between men and women in my view completely demonises men and makes everyone believe we are aggressive and can’t respect our women,” he says.

Ali says there is nothing empowering about niqab or the burqa, which he sees as nothing more than a tool used by fundamentalist men to control women. The debates around the niqab or the burqa, he feels, also homogenise Muslims and people fail to realise the cultural differences among several Muslim countries.

As for the recent debate raging over the niqab in Canada, Ali feels anyone who wants to become a Canadian citizen should have no problem in showing their face to a judge.

“It’s the law and I feel it’s completely unnecessary for anyone to say they won’t take off the niqab, pardon my words, but I think it’s BS for someone to say niqab is religious because it’s not,” he says.

It’s a typical weekend for Homa Abolfathi at the Squamish Valley Campground, where she lives with her husband, Ali Abolfathi, and two children. She is preparing a sumptuous meal for her kids and some friends who are visiting them from Vancouver.

The Abolfathis, originally from Iran, live like a very typical Canadian family in a rather atypical setting. Ali runs the campground on Squamish Valley and Homa works as a home maker, helping kids with their homework and taking them to their school in West Vancouver every day.

Homa rarely covers her head in Canada, but when she is packing her bags to visit friends and family in Iran, she usually packs a few hijabs with her. After the Islamic revolution, it’s mandatory to wear the hijab in Iran in public but rules around it are getting much more relaxed in Iran, Homa says.

Even the government, mindful of a rapidly secularising middle class, has reined in the police and asked it to enforce the law with respect to women and their dignity. Still, it’s almost rare to see women in a public place without a hijab although the style can change with setting. In a restaurant with friends and family, women are still able to get away with wearing a hijab which doesn’t cover the head. In more solemn settings, such as a funeral, women will tend to cover their head properly.

“If you go to a holy shrine, it’s a much more restricted way but the idea behind the hijab is to wear it for modesty,” she says.

Homa was born in South-West region of Iran and grew up before the Islamic revolution when even the hijab was optional. But niqab and burqa were unheard of in the parts where she grew up and were worn in only south Iran. niqab isn’t mandated by religion but by culture, she says, and for many the head covering really comes down to dressing modestly in public.

“I don’t wear it when I’m in Canada but sometimes I do miss not wearing it,” she says.

As for the controversy over the niqab, both Homa and Ali say they respect the woman’s right to wear the niqab but not when it conflicts with the law. Prime Minister Stephen Harper, Ali says, might have used the issue cynically in this election but he agrees that law should be applied uniformly.

“You can’t walk in someone’s country and expect them to change the laws because of specific culture and religion, everyone is and should be equal before the law,” he says.

Even in Iran, Ali says, a woman would be expected to reveal her face for a government-issued identity card.

Patricia Marini says

Thank you all for your informative articles about this subject ,especially to you, Gagandeep for your in bold letters statement, my believe exactly.!!Patricia

Dave Colwell says

Exactly!!