The oldest features in our Squamish built environment are likely pilings. No buildings survive older than about 1910. The last bighouse at Seaichem was taken by the river long ago.

Other than those used for dock structures (covered under fill), the oldest surviving pilings are at the mouth of the Squamish River and in the Upper Mamquam Blind Channel at Scott Crescent.

They were used for log drives. Before the first railway was built to the waterfront in 1910, and long before truck roads, logs were transported by the river.

The “Blind Channel” was at that time the East Branch of the Squamish which was actively used as favoured canoe route. It was also used for moving logs. The big stumps on the golf course are from cedars cut and floated down the old Mamquam to today’s Blind Channel.

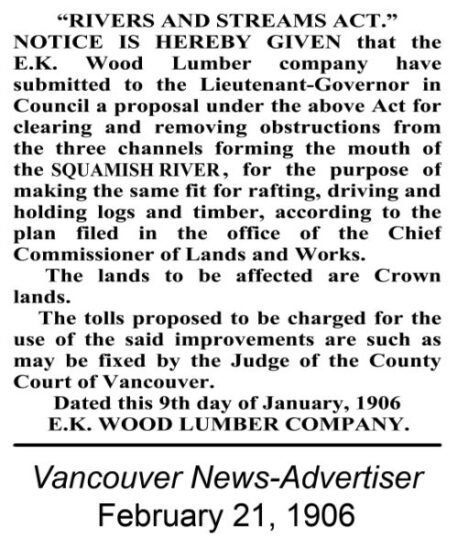

We have a February 1906 ‘birth certificate’ for the row of pilings in the Upper Channel along Scott Crescent.

As they are on a crown water lot, the E.K. Wood Lumber Co. had to apply to the Province to install them according to a submitted plan for purposes of making the river “fit for rafting, driving and holding logs and timber.”

These Rivers and Streams Act rules were originally imported from eastern Canada, which had a century of experience in log drives and administering use of rivers by the timber industry.

E.K. Wood Lumber was based in San Francisco but had eastern origins, as well. They arrived here in 1903 and had a mill at Bellingham and contracts to supply the Panama Canal construction project with timbers.

Development of the west coast forest industry in the early decades involved two cultures working together. The river drive culture of the Ottawa, the Saginaw, New Brunswick and Maine collaborated with the local river knowledge and cedar dugout canoe culture of the Coast Salish peoples.

Before the railway era came to the Squamish Valley with all of its changes, Squamish Nation men enjoyed a privileged place in the forest industry, especially on the river and booming grounds here and on the waterfront in Burrard Inlet.

As river boss for its log driving operations, E.K. Woods hired Xwalacktun Charlie Douglas. To design the company’s boom across the mouth of the Squamish to catch the logs coming down the river, the company hired a Snohomish man and “expert in that line”, Neil Spithill from Everett, Washington.

This heyday of employment in niche roles in the timber industry expressed itself in grand potlatches – some of the last held in the valley, including one co-hosted by ‘Skookum Charlie’ Douglas himself in 1905. It also provided the means to finance political action, such as Sahp-luk Joe Capilano’s trip to England to see King Edward VII in 1906.

Log handling on the river and in the booming grounds was also dangerous work. Between 1902 and 1910 over a dozen drownings in Squamish River operations are recorded, including of Squamish Nation men.

Charlie Douglas hired his future son-in-law Xwalxwalkn Austin Harry as part of his log drive crew. In a 1963 interview Austin recalled working as a teenager 25 miles up the river at the Ashlu flats, “standing in icy water up to my chest, rolling logs into the river so they would drift down in the current.”

Austin Harry’s sons George and Ernie would also spend most of their working lives on the Squamish waterfront in the log handling trade.

Our Upper Mamquam Blind Channel pilings have been used by many loggers since ‘Skookum Charlie’ Douglas’ time, including by the Madill family for tying up booms of cottonwood bolts to be shipped to the BC Sugar refinery for barrel making.

Today they host bird nesting boxes, and many stories. They remind us that this was once – and still is – a river.

Eric Andersen is a local historian and a District of Squamish councillor.

Corinne Lonsdale says

Thank you Eric…what an interesting article. I remember Austin Harry. He had a wicked breathing issue…probably some type of asthma and maybe from working on the waterfront in the elements for so many years.

J. Singh Biln says

Hi Eric;

How truly fascinating! I love local history, particularly logging and railroads. I see remnants of old pilings land wonder about the efforts it took to drive them and also how they were subsequently used. Thanks for sharing this with us.

Singh

Dianne says

Too bad they closed the river off… now stagnant water in the upper area