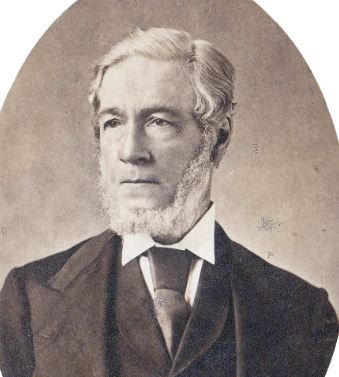

Alexander Caulfield Anderson was appointed in 1876 as the first Inspector of Fisheries for British Columbia. His first Pacific Fisheries report was in large part written under a canvas tent on what is now the Downtown Squamish waterfront during a rainy late November day that same year.

A.C. Anderson (after whom Anderson Lake is named) had just completed a plan for the establishment of Squamish Valley reserves together with fellow commissioners of the joint federal-provincial Indian Reserve Commission, Gilbert Martin Sproat and Archibald McKinlay.

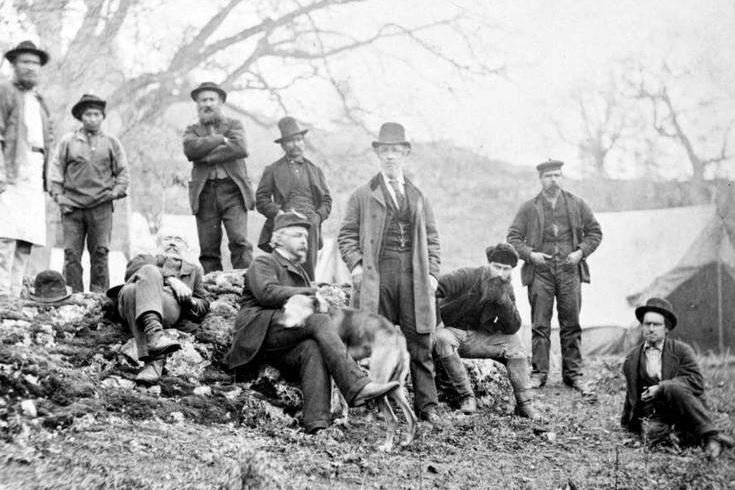

Hosted and guided by two senior local chiefs – Chief Joseph (Mak-nah-til-tun) of Stá7mes and Chief Paul of Yekwaupsum, Anderson and the IRC party had spent a week exploring the river all the way up past the Ashlu confluence – during the height of the chum salmon run.

According to Commissioner Sproat, “Countless salmon, dead, dying or fatigued, were seen in the river. We could have killed scores of them with the paddles. The smell of the dead salmon on the banks was offensive.” (G.M. Sproat diary, Nov. 27, 1876)

And Commissioner McKinlay: “Salmon by tens of thousands dead & dying. It is truly a pitiful sight to see them but it must be for some wise end. Gulls and eagles are to be seen in every direction feeding on the dead fish.” (A. McKinlay diary, Nov. 22, 1876).

During a long earlier career serving at several Pacific Northwest posts of the Hudson’s Bay Company in trading with indigenous peoples, A.C. Anderson had obtained significant experience with fisheries. He was a keen observer and note-taker concerning fish species, names for them in local languages, salmon life cycles, and indigenous modes of fishing. Each of these topics are treated in the Pacific Fisheries Inspector’s report for 1876.

In this report and in previous writings, and at a time when there was poor access to scientific knowledge, Anderson recommended careful attention to the indigenous names for the various Pacific salmon species – “that clue which might else be afforded by the native nomenclature.”

In the Squamish language, the names of the salmon species are: kwõx̲weth (coho); tl’élx̲xel (chinook); kw´ó:lexw (chum); húheliya (pink); and sthéqi (sockeye, which the Squamish people harvested in the lower Fraser or traded for).

Anderson drew directly on his Squamish River observations and host informants for his report, not only concerning salmon but also about the eulachon fishery:

“I found on enquiry, that these fish enter the river, as elsewhere, early in the spring, and ascend as high as the head of the island of Stâ-â-mis, forming the delta; thence, after spawning, returning to the sea.”

Throughout his tenure as Pacific Fisheries Inspector, Anderson was a vigorous defender of indigenous peoples’ mode of fishing and the principle of their hereditary rights to subsistence fisheries – against the skepticism and opposition of Ottawa bureaucrats, the cannery industry and other business interests.

In his Squamish report Anderson related that, “the native modes of fishing, simple but efficacious, throughout the Province, are in all respects unobjectionable and economical; and any interference with their proceedings would be unadvisable, save when, through bad example, they infringe a general protective law.”

A Fisheries Act applying to British Columbia was introduced in 1877. It was based on eastern Canadian experience and conditions, with little consideration of west coast circumstances. Salmon Fishery Regulations were introduced the following year, which banned use of nets in non-tidal and fresh waters – completely overlooking impacts on indigenous peoples.

Anderson had some prominent supporters behind his concerns. Chief Justice Matthew Begbie suggested exemption from the new regulations for “Indians fishing by their accustomed methods for the support of themselves or their tribes.” Indian Reserves Commissioner G.M. Sproat pointed out that, “The Government of England, 25 years ago, might as well have prohibited the cultivation of potatoes by the Irish.”

Protecting traditional fishing sites was a top priority of the local chiefs and the Sproat-Anderson-McKinlay Commission in 1876. As Anderson related, “It is our intention to assign all the village sites and fishing stations pointed out to us by the natives as desired by them.”

Among the fishing stations designated as Indian Reserve was Mamquam Island (I.R. No.20, purchased by the PGE Railway in 1914 and recently acquired by the District of Squamish), directly north of the Squamish Adventure Centre, which was traditionally used as the central camping, harvesting and processing station for the annual spring eulachon fishery.

Canoeing down the East Branch of the Squamish (the slough behind the high school, Capilano University and Adventure Centre) on his way to their base camp at or very near today’s Xwu’nekw Park at the foot of Victoria and Main Streets, Anderson was feeling nostalgic, recalling Hudson’s Bay Company days:

“Preliminary to arrival our Indian Canoe-men, who are in the highest spirits, brought our two remaining canoes in line, and, keeping slow stroke in unison, sang an agreeable but rather plaintive chorus in admirable time – reminding some of us of bygone days when the more lively paddle-song of the French Canadian voyageurs was a familiar sound.”

As Fisheries Inspector, A.C. Anderson continued “to exercise a watchful surveillance for the common benefit” until his death in 1884. He contributed practical, sensitive observations and recommendations on fisheries regulation, conservation and restoration issues which persist to the present day.

Peter Jacobs says

This is a nice summary provides a good basis for understanding the (mis)management of salmon since.

1) I would reword the part, though about lack of access to scientific knowlege about the salmon. The Squamish people and other First Nations have plenty of scientific knowledge about the salmon. We understood how to live with the salmon and harvest them as needed. there is a lot of scientific knowledge that go into those practises, some of this knowledge only recently acknowledged by western science. for example, no one in western science was talking about the role of salmon to the entire ecosystem on the coast here, not just as food for animals but as nourishment for the water and the plants. we cannot have a northwest coast environment for very long without salmon.

2) an interesting language observation, all those salmon names, except for sockeye, are not the contemporary terms for the different species. I wonder if he says who his consultants were. that would be helpful in determining where these terms came from. the terms we do have come from people who were alive just a generation after this commission.

Huy chexw a (thank you),

T’naxwtn

Eric Andersen says

Thank you for your observations, Peter Jacobs! I believe A.C. Anderson would support your comments on First Nations scientific knowledge entirely. The comments on the Squamish chum salmon run I’ve retrieved and included from Sproat and McKinlay I thought illustrated well the ignorance of even well travelled settlers of the 19th century.

Anderson, as best as I can puzzle out from his transcription efforts and various spellings in several of his writings, borrowed Halq’emeylem and Upper Fraser terms for salmon species, as well as noting the Squamish terms. It is difficult to say. But he did make unusual effort for his time. The Squamish language terms quoted in the article come from the 2011 Squamish Nation Dictionary Project publication, which I should have cited. One is always constrained for space in a popular article.

Anderson’s key consultant on salmon and eulachon fisheries during his Squamish Valley visit was almost certainly Chief Joseph — whose name is rendered by F.M. Sproat as ‘Mak-nah-til-tun’. (I have always wondered if this name has continued to be passed down, and how it might be rendered in today’s spelling practice.)

Thank you!

J. Singh Biln says

Eric; Thank you so much for another informative and interesting article on local history. I hope that you will continue writing these articles for the benefit of local citizens of all ages. Thanks again.